The Fourteenth District Court of Appeals of Texas has dismissed a lawsuit brought by the driver of a car that was struck by a Houston engine that was backing up. Emmitt Wilson filed the suit in state court naming the city and firefighter Jason Carroll as defendants

Carroll was driving Engine 43 on April 26, 2019 when he backed into Wilson’s vehicle while trying to reach the scene of a prior accident. As explained in the decision:

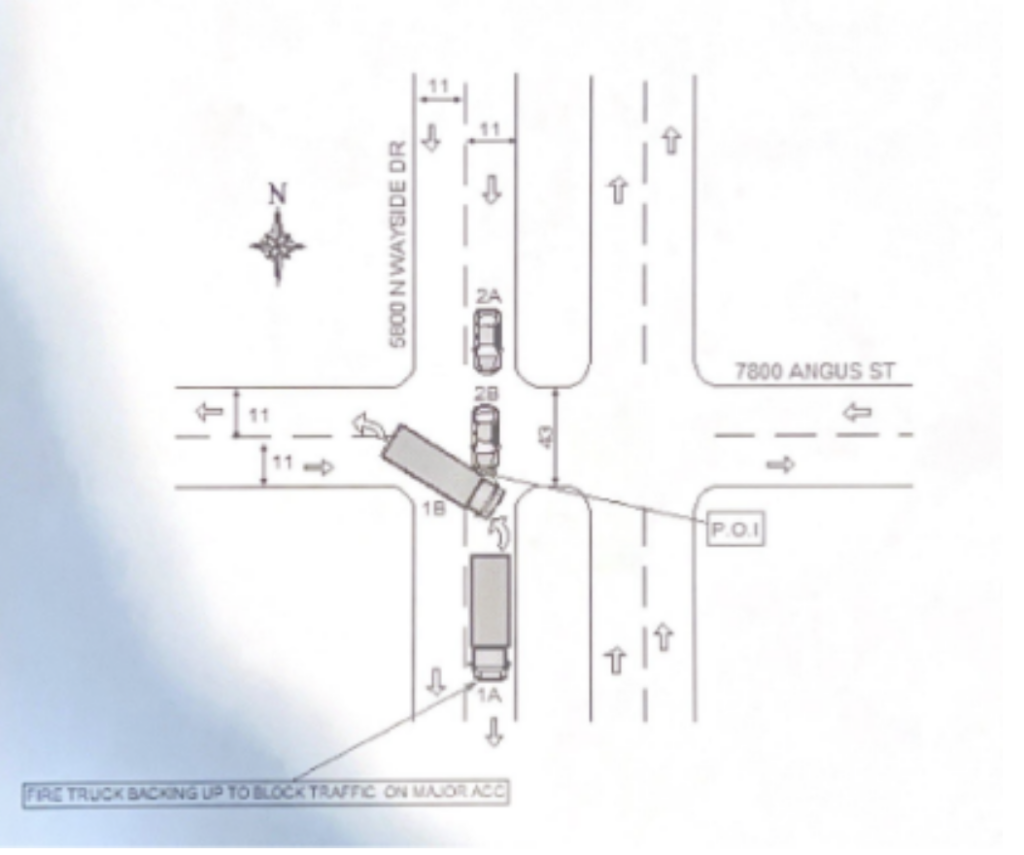

- Engine 43 had been dispatched to respond to an 18-wheeler-sedan collision on the northbound side of Wayside, north of Angus.

- Jason Carroll, the fire engine operator driving Engine 43, concluded he needed to back up the engine to negotiate the heavy traffic conditions in route.

- When Engine 43 began backing up with his spotter guiding, so did Wilson.

- But when Wilson ran out of room he had to stop before colliding with a vehicle behind him. Engine 43 continued and collided into Wilson’s vehicle.

Here is a scene diagram included in the decision.

Wilson’s suit alleged negligence. The city claimed it had official immunity protection and filed a motion for summary judgment. Carroll was dismissed from the suit, but the city’s liability hinged on whether Carroll would have been liable. The trial court denied the city’s motion concluding it was not entitled to immunity. The city appealed the trial court’s ruling to the Fourteenth District Court of Appeals.

Quoting from the court of appeals (citations and quotation marks removed to facilitate reading):

- A governmental employee is entitled to official immunity: (1) for the performance of discretionary duties; (2) within the scope of the employee’s authority; (3) provided the employee acts in good faith.

- The record establishes as a matter of law that Carroll was conducting a discretionary duty at the time of the collision, as operation of an emergency vehicle in an emergency situation is a discretionary duty.

- The fact that Carrol had slowed, put the engine in reverse, and turned off the siren to hear his spotter on the radio did not remove the fact that he was still trying to get to the accident site—the emergency or the discretionary nature of Carroll’s activities at the time remained.

- Because the evidence was uncontroverted that Carrol was operating Engine 43 in the course of an emergency response to a vehicle accident, and Carroll’s affidavit illustrates the various decisions he made in the course of driving Engine 43 leading up to the collision—including determining the proper route to the accident, whether to keep the emergency siren and lights engaged while backing up, whether and how many spotters he should have while performing the reverse maneuver—we conclude that the Carrol was performing discretionary duties at the time of the incident.

- Thus, to the extent the trial court’s denial of summary judgment was based on a finding that the City failed to conclusively establish that Carrol’s acts were discretionary duties at the time of the collision, such finding was erroneous.

- We next consider the trial court’s implicit finding that the City failed to conclusively establish that Carrol was acting in good faith at the time of the incident.

- The good-faith standard is analogous to an abuse-of-discretion standard that protects all but the plainly incompetent or those who knowingly violate the law.

- In this context, good faith depends on how a reasonably prudent fire engine operator could have assessed both the need to which the fire engine operator was responding and the risks of the fire engine operator’s course of action, based on the fire engine operator’s perception of the facts at the time of the event.

- On this record, the City satisfied its burden to prove conclusively that Carroll was acting in good faith at the time in question.

- Thus, to the extent the trial court’s denial of summary judgment was based on a finding that the City failed to conclusively establish that Carrol was acting in good faith at the time in question, such finding was erroneous.

- We next consider the trial court’s implicit finding that the that Wilson offered evidence that no reasonable officer in Carroll’s position could have believed that the facts were such that they justified Carroll’s conduct.

- Wilson did not offer any evidence on good faith, to inquire into what a reasonable officer could have believed.

- Wilson’s evidence fails to adequately rebut either of the contested elements of governmental immunity.

- On this record, to the extent the trial court’s denial of summary judgment was based on a finding that Wilson had adequately rebutted the City’s proof, we conclude such holding erroneous.

- Accordingly, with sufficient proof showing that Carroll would not be liable because he is protected by official immunity, the trial court erred in denying the City’s summary-judgment based on official immunity.

- Having sustained the City’s complaint that the trial court erred in denying its summary judgment on its official immunity grounds.

- We reverse and render a judgment dismissing Wilson’s action.

Here is a copy of the decision:

Fire Law Blog Fire Service and Public Safety Legal Issues Blog by Curt Varone

Fire Law Blog Fire Service and Public Safety Legal Issues Blog by Curt Varone